By Benjamin H. George, ASLA, and Peter Summerlin, ASLA

November 5, 2019 by LAM Staff

From the NOVEMBER 2019 ISSUE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE.

In 1982 a new tool landed on the desks of engineers that would revolutionize the construction and design industries. That tool, eventually known as AutoCAD, ushered computer-aided design into the field with the goal of increased accuracy and efficiency. In the decades since, a variety of software programs have become embedded in nearly every step of the design process, from site inventory and analysis to final project deliverables and beyond. Software has evolved from tools to represent design to those actually affecting design ideas. It’s more than just software, as emerging technology such as drones, virtual reality (VR), and 3-D printers have found their way into offices. Whereas it was once adequate to master only AutoCAD, Photoshop, and SketchUp, many firms are now expected to collaborate and communicate using technology beyond this “big three.”

As firms wrestle with their software decisions and changing collaboration needs, knowledge of technology trends across the industry can be a valuable tool. With this in mind, ASLA’s Digital Technology Professional Practice Network (DTPPN) teamed with professors from Utah State University and Mississippi State University to document and assess current developments in the profession. The survey was sent to a third of ASLA’s members and garnered 482 responses, 72 percent of whom were full members of ASLA, and 17 percent associate members. When compared to surveys from previous years, the findings paint a picture of a profession in the midst of a watershed moment in how technology is used. While the big three are still staples, there are now many alternatives and add-ons to augment and expand the design workflow.

The representation tool explosion

The emergence of 3-D modeling programs over the past 25 years has transformed the ways many firms represent design ideas. Today, our survey data indicates these modeling programs are more prevalent than ever, but supplemented with renderers, plug-ins, and add-ons. The addition of 3-D rendering software has changed the process: What was a two-dimensional export from SketchUp is now a SketchUp model, rendered in Lumion, and post-processed in Photoshop. A choppy animation of SketchUp scenes might now be a parametric design generated in Grasshopper and viewed in VR. The goal is still the same: communicate a vision to the client effectively and convincingly. Paul Drummond, ASLA, of the multidisciplinary firm Snøhetta explains that frequently “clients are not visual thinkers, and we are often giving them a variety of graphic visualizations to see what sticks.”

This is not to say that technology is the only means of achieving this goal, but based on the survey results, firms are rapidly adopting renderers and plug-ins. In a 2016 DTPPN survey, 18 percent of respondents used Lumion; now that number is at 30 percent. Similarly, a 2014 DTPPN survey found 8 percent of respondents used Land F/X, while today 33 percent of firms use the plug-in. There is also a strong correlation between the use of renderers such as Lumion and Photoshop. For many landscape architects, it seems that an untouched export from a modeling program or renderer isn’t sufficient for their vision. Drew Hill, Student ASLA, a landscape designer at OJB Landscape Architecture, says, “You can instantly recognize a Lumion render, so I always added additional filters and entourage [people and other elements] to give it my own feel.”

Modeling and rendering programs also lack components that landscape architects often use. “There are limitations in the entourage,” said Mark Johnson, FASLA, president of Civitas, while relating a story of a bicycle-oriented project in the Czech Republic. Their modeling program had only one cyclist in the default entourage, so additional cyclists were added in Photoshop for the final presentation.

According to the survey results, another shift involves the ways clients experience the design. Jessica Fernandez, ASLA, a landscape architect and owner of the visualization firm Alpha Design Studio, has found more and more of her clients expect an immersive experience, and says that her firm now seeks to provide a “virtual walk-through of a site or space that seamlessly incorporates a series of 360-degree panoramas, where the client is not entirely free to roam a virtual world, but can experience multiple vantage points in a controlled and user-friendly setting.” Unlike a software package with set features, VR (currently used by 27 percent of firms) can be molded to a variety of uses, and it has spurred a variety of research efforts on VR in landscape architecture. Notable examples include research on immersive design funded by Intel at Utah State University (by coauthor Benjamin H. George, ASLA); Andrew Sargeant, Associate ASLA, who researched video game engines and VR for his Landscape Architecture Foundation fellowship; and April Philips Design Works’ experimentation combining cinematography and VR. These and other efforts could help mold VR to the unique needs of landscape architects in ways not seen with other new technologies.

Is AutoCAD still ubiquitous?

The survey results show that AutoCAD remains the consensus drafting software, as 82 percent of respondents report that their firms use AutoCAD weekly or daily. Given the proliferation of drafting software options, including some designed specifically for landscape architecture, why does AutoCAD retain its position as the industry standard? Eric Berg, ASLA, a senior associate of Pacific Coast Land Design in Ventura, California, describes it this way: “There have always been alternatives, but AutoCAD offered the first opportunity to collaborate and coordinate multiple users [across disciplines]. There is too much institutional knowledge in most firms to effectively pull a 180 and switch to something new and different. The opportunity cost of leaving AutoCAD is too great.”

It may not be long, however, before the cost of working solely in AutoCAD could be too great. Berg senses a change that could shake up AutoCAD’s hold on the industry. “There is a massive demand to break away from the black screen with multicolored, two-dimensional lines. Traditional CAD-to-deliverable workflows are very complex. They may involve drafting in AutoCAD, exporting that to Adobe Illustrator for plan graphic rendering, exporting to SketchUp for modeling, and then to Photoshop for labor-intensive rendering—only to have to redo it all when the design changes even slightly. The ideal is that, as the design updates, everything downstream updates along with it.”

For Berg, supplementing AutoCAD with a program such as Vectorworks (used by 13 percent of firms, up from 12 percent in 2016 and 9 percent in 2014) allows him to approach the goal of updating across multiple design documents. “Vectorworks has allowed us to get much closer to that goal than AutoCAD ever did, and hopefully it will only continue to get better.” Berg now produces educational material with Vectorworks to help demonstrate the ways landscape architects can integrate the AutoCAD alternative into their workflows. Andrea Hansen Phillips, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia and principal of the design firm Datum Digital Studio, similarly sees a future where, while the big three remain, there will be a shift over the next five years resulting “in the expansion of software tools being used in practice on a regular basis,” such as plug-ins and coding. Phillips believes these changes will be financially driven, as “it is orders of magnitude more expensive to hire outside consultants” than to train employees.

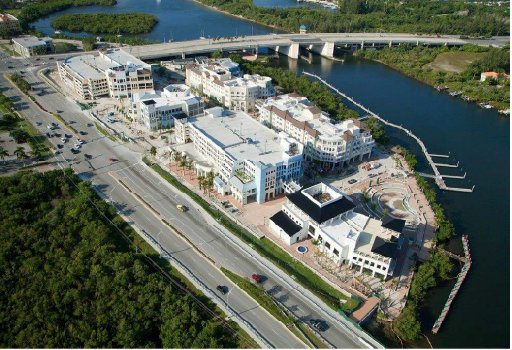

Other software packages have seen increased usage from previous years. While SketchUp is the most commonly used modeling program (83 percent of firms use it, up from 81 percent in 2016, 69 percent in 2014), 28 percent are now using Rhino at least monthly, up from 25 percent in 2016 and 8 percent in 2014. The landscape architect Emily O’Mahoney, FASLA, of 2GHO noted that although 2GHO uses SketchUp for 3-D modeling, they use Rhino when they have staff who are proficient with it, as it allows for better modeling of landscape forms. Programs such as Revit and Civil 3D have also risen in usage—Revit is currently used by 32 percent of firms and Civil 3D by 48 percent of firms. As outlined by Aidan Ackerman, ASLA, in his article “The BIM That Binds” (LAM, June 2019), for many, the adoption of Revit is driven by collaboration with architecture firms that also use Revit. Seth Bockholt, ASLA, the owner of a landscape architecture firm in Park City, Utah, describes a scenario many landscape architects face. “If our designs don’t make it to the Revit presentation at the architect’s office, then [they’re] never seen and fully valued and integrated into the design process.”

Are landscape architects destined to adopt what allows us to collaborate? Perhaps it’s the result of a profession at the intersection of multiple disciplines. Bockholt also observes that “architects don’t have to leave Revit if they don’t want to. As a landscape architect, you have to speak a lot of different languages and use a lot of different platforms because you are collaborating with so many different people and industry segments.” Whereas before it was sufficient to be able to communicate ideas with allied fields, now we need to communicate data, and that requires an additional level of software proficiency. Phillips believes that “the increase in complexity and scale of many landscape projects…[is] making the use of GIS analysis, simulation, data visualization, and generative modeling more important than ever.”

Where does GIS fit?

Surprisingly, respondents report GIS has relatively low importance to their workflow. Sixty percent of practitioners report using GIS only a few times a year or not at all. And of those using the software, many expressed that they could easily complete their work without it. For several respondents, the use of GIS is limited to understanding the context of a site. Karen Skafte, ASLA, a principal at Ground Reconsidered in Philadelphia, says her firm uses GIS for a single contract, but otherwise, it is not important for its workflow. Johnson expressed the attitude of many landscape architects, saying Civitas “rarely uses it because the size of a site where GIS is appropriate is too large for the projects we work on,” and “often the cell size is too coarse and the resolution isn’t accurate enough to adequately inform site-scale design decisions.”

Although the survey consensus reported a low level of importance for GIS in office workflows, it’s undeniably critical for some firms. “GIS is absolutely fundamental for what we do,” says Glen Busch, a GIS analyst at the multidisciplinary planning firm Bio-West in Logan, Utah. “When we start getting into corridors, like a highway project, or an environmental assessment, we are using GIS to do resource evaluation and analysis of different impacts.” AutoCAD is needed to make final design decisions, but “GIS is good for interfacing with all kinds of spatial information and performing analysis.”

A new big three or a new paradigm?

What do we make of the diversification of software used in the profession? Is the profession sifting through the latest software to establish a new big three? It doesn’t seem that way. Instead, the survey results suggest a new paradigm, where firms use a collection of software packages and emerging technology to expand their capabilities in design, communication, and collaboration. Phillips expects the burden of learning this new software won’t be as great because these tools are being integrated into current landscape architecture curricula. There is a “new cohort of emerging designers equipped with the software skills to help firms adopt new technologies and methodologies.”

Landscape architects are rapidly adopting emerging technologies. Image courtesy Benjamin H. George, ASLA.

What is known is that firms are investing in emerging software and technologies at a high rate: 55 percent have adopted the use of drones, 42 percent are integrating building information modeling (BIM), and 27 percent are using VR. Additionally, strong correlational data suggests the majority of firms that invest in one emerging area are investing in another. These investments come at a price, though. Licenses and hardware are expensive, but billable hours lost learning how to integrate the technology can be more costly. As Fernandez observes, “As a small studio, we also must pay close attention to the cost of new software or technology compared to its profit potential for the company. We evaluate the up-front expense of the program, associated technology, and training involved against our skill sets and how quickly we can turn that venture into fiscal gain.”

Recent survey data also shows that firms investing in software training through dedicated IT staff or company-sponsored training are more likely to use software outside the big three. Conversely, firms that expect employees to train themselves have a high interest in adopting new technology but a negative correlation regarding the value of the new technology they have adopted. This suggests that these firms are interested in adopting new technology, but their ad hoc training approach may be resulting in a deficient application of emerging technologies that fall short of firms’ expectations and could benefit from more formal training procedures.

Ultimately, the primary takeaway from this national survey is that technology use in the field is more diverse than ever and will likely expand. Firms must grapple with which of the many digital tools are most appropriate for their teams and their collaborations to be effective and efficient. Finding those appropriate tools, digital or otherwise, is vital. As Todd McCurdy, FASLA, of Huitt-Zollars says, “Don’t drive screws with a hammer. The best thing is to use the right tool for the job.” With the current growth in software offerings, landscape architects can be optimistic about finding the right tools.

Benjamin H. George, ASLA, is an assistant professor in the Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning Department at Utah State University. Peter Summerlin, ASLA, is an assistant professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Mississippi State University.

Source: https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2019/11/05/get-with-the-program/